A few weeks ago, Ben Goldacre wrote, "If you do not link to primary sources, you are dead to me."

Seems fair enough to me. So this blog post provides some of the evidence and some of the links to primary sources for my TV programme “23 Week Babies: The Price of Life”, broadcast on BBC2 at 9pm on March 9th 2011. A 2 minute trail is here.

My view is that there are better places than television for all the facts and figures that surround the kinds of programme I make. So this document is for the nerds and geeks and anyone else who’s interested in the numbers. And for anyone who wants to hold me accountable.

Feel free to email me, or add comments. I hoping that if there are errors they aren't too terrible.

Please do join in the debate about the programme:

Twitter: #23weekbabies

Adam Wishart

9 March 2011

Twitter: @adamswishart

Website: www.adamwishart.info

Facebook: www.facebook.com/adamwishart

Email: adam (at) adamwishart.info

CLAIM ONE: Chances of survival for 23 Weekers

For babies born in the 23rd week, survival odds are as follows:

- 91 out of 100 babies die in hospital in the first weeks of life.

- 9 out of 100 babies leave hospital.

Of those 9:

- 2 are severely disabled

- 4 are moderately disabled

- 2 have some impairment

- 1 survives unscathed.

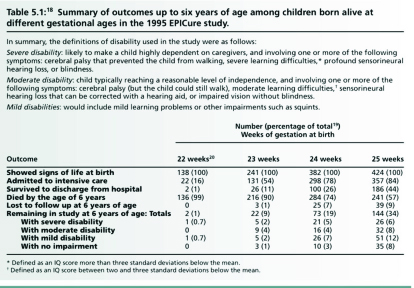

How do we know this? The best research on the outcomes for extremely premature babies is the EPICURE study from the Nuffield Council of Bioethics Report, “Critical Care Decisions in fetal and neonatal medicine: ethical issues”. (2006) The researchers studied all the premature babies born during ten months in 1995 (1185 babies in total) and then followed up when they were two, six, and ten years of age.

This is the key table, from page 71 of the report.

Surely, you might say, this evidence is out of date: the babies were first surveyed more than 16 years ago and, what with the general advancement of science, things must have moved on. If I may, I'll come back to the discussion of this point at the end of these notes, after looking at some of the other claims in the film.

CLAIM TWO: Rates of survival

Another key claim in the film is that, in the words of Imogen Morgan the Clinical Director of the neonatal ward at the Birmingham’s Women’s Hospital, “The proportion of 23 week babies surviving isn't increasing… We are close to a limit of nature.”

I also say that whilst there has been little improvement for babies born in the 23rd week, there has been significant improvement in babies born in the 24th week and above.

The key paper for this proposition is from a series of studies from the Trent region of the UK : "Survival of extremely premature babies in a geographically defined population: prospective cohort study of 1994-199 compared with 2000-5."

Here they studied all the babies born in one geographical region, Trent*. They compared the outcomes for babies born between 1994-1999 and those born between 2000-2005.

What did they discover? "Survival of infants born at 24 and 25 weeks of gestation has significantly increased. Although over half the cohort of infants born at 23 weeks was admitted to neonatal intensive care, there was no improvement in survival at this gestation."

But, I hear you ask, that only takes us to 2005, which is 6 years ago. Bear with me, please.

* It’s better to look at these so-called cohorts because there is less bias than if you looked at, say, just one hospital which might be significantly better or worse than others.

CLAIM THREE: Number of 23 weekers born

The film says that “a few hundred” babies are born in the 23 week of pregnancy each year. This is an estimate of the right order of magnitude, extrapolating from the fact that there were a total of 110 babies born at 23 weeks in most, but not all, neonatal units in England (from the Neonatal Data Analysis Unit: Neonatal Specialist Care in England: Report on Mortality in 2009). As the figures don’t include every single English unit – and nor do they include any units in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland – I extrapolated to “a few hundred”. A bit woolly, but the best we could do with the available data.

CLAIM FOUR: Cost to the NHS

The film says that the NHS spends about £10 million a year on these babies.

This is a simple calculation from these facts:

- One night for one baby in a neonatal intensive care costs around £1000 in terms of equipment, staff, overheads and so on.

- On average, these babies stay in hospital for about 35 days

- Say there are approximately 300 hundred babies per year

The estimate for the cost of baby Matilda, who goes home after 139 days is about £150,000.

The cost is rising: according to the commissioners in the West Midlands the total cost for neonatal services in that area rose by 10% last year. Whether that is the whole of the trend or a blip is more difficult to calculate.

Other considerations:

- Within the total NHS budget of about £100 billion, the figure of £10 million is pretty insignificant.

- As 8 out of 9 of the surviving babies will be disabled, they will continue to cost the NHS throughout their lives, so these figures are just the start of the cost of these babies to the NHS.

- As Heather Rutherford explains in the film, the care these people receive is greatly reduced once they hit the age of 18

- In the film, I ask Ann Aukett, a community paediatric who looks after survivors, if she is able to give the survivors the care they need, and she categorically says no. Whilst making the film, I met a 23 week baby who was two years old and who had had to wait a whole year for a physiotherapy appointment. Which suggests to me that we are not caring for these babies properly once they leave hospital, even before they are 18.

- I also saw a baby who was most likely born in the 22 week (often it is not possible to date conception exactly), but had been resuscitated despite the guidelines. So as a nation we spent a few thousand pounds keeping a baby alive that would almost inevitably die, and yet we couldn't provide simple therapy for a child that modern medicine had allowed to survive, but disabled.

CLAIM FIVE: Britain amongst worst premature birth rates in Europe

The European Perinatal Health Report collected data from across Europe in 2004 and published it in 2008. The data for premature births under 32 weeks is on page 131. (Below 32 weeks, of course, isn't the same as 23 weeks but the data is not available for 23-weeks and choosing the later range does mean that the numbers are quite large, and therefore more accurate. As the numbers of below 32 weekers goes up, then so does the absolute number of 23 weekers.)

Percentage of babies born prematurely at 32-weeks or less, by country:

- England and Wales, Hungary, Austria = 1.4% [Highest percentage]

- Germany = 1.3%

- Denmark = 1.1%

- Italy, Ireland, = 1%

- Sweden, France, Greece, Finland = 0.9%

- Spain = 0.8%

- Malta = 0.7%

In other words, Britain has about fifty per cent more babies born (per capita) in prematurity than some other European countries.

CLAIM SIX: Link between premature births and deprivation

The epidemiologists state the evidence the best: "the incidence of very preterm birth is nearly twice as high in the most deprived areas compared to the least deprived areas" (Socioeconomic inequalities in survival and provision of neonatal care: population based study of very preterm infants.)

But it seems very difficult to discover why it is that people in deprivation have higher incidence of preterm birth. Many reasons are being studied – including smoking, alcohol and non-attendance of pre-natal check-ups - but the answer is not yet clear.

CLAIM SEVEN: Intervention levels increasing, but survival rates not

Towards the end of the film, neonatal consultant Anne Aukett explains that 23 week babies are enduring more and more medical intervention. How do we know this?

Going back to the Trent Study mentioned in Claim 2 above, looking at the table on the second page, it says that between 1994-1999 the average time that 23 week babies spent on the ward was 22.9 days. And then between 2000-2005 that number had gone up to 34 days. So babies now spend nearly an extra two weeks on the ward, during which time they have a variety of medical interventions – often including ventilators down their throats and needles into their arms - which cause some pain and discomfort.

These extra two weeks of pain have failed to provide any benefit according to the Trent Study.

A different cohort published last year came to similar conclusions. “Survival in infants live born at less than 24 weeks’ gestation: the hidden morbidity of non-survivors” concludes that "Over the last 15 years, increasing numbers of babies at less than 24 weeks have received active resuscitation. Overall survival has not changed, but non survivors have endured significantly longer durations of intensive care." This includes data up to 2007.

CLAIM EIGHT: Outcomes not improving over last 15 years

Throughout the film – and these notes - there is the tacit idea that the evidence as outlined above gleened from reports over the last 15 years remains true. But perhaps the outcomes have radically changed in the last couple years. Perhaps there is some unpublished data which suggests that there is a radical new treatment that is prolonging the lives of 23 week babies.

The first thing to note is that these studies are really the best evidence we have. In all these cohort studies there is very limited data from this year or last year. Part of the trouble is that it takes time, years, to collect and assess the data. Frankly these studies much be a bureaucratic nightmare: just imagine trying to follow a couple of thousand people for years, when we all lead such transient lives.

Another problem is that to really understand the outcomes we have to wait for children to grow up. The cohort of the EPICURE study is now only 16 years old. And, as with all of our lives, long term outcomes is vitally important.

But just to check that there were no new studies that would radically change our view, I phoned Elizabeth Draper, the professor of perinatal and paediatric epidemiology at Leicester University. She is the lead statistician on both the big cohorts in the UK, EPICURE and Trent. They continue to collect data. I asked her whether there was any evidence that survival rates for 23 week babies have increased in the last few years. Her reply was that there wasn't any statistically significant evidence.

The real problem is that the numbers of 23 week babies is so small it is difficult to create a powerful enough study to reveal it.

CLAIM NINE: Other countries have better survival rates?

Well in fact this isn’t my claim. But it is often mooted on the radio and on discussion boards. People claim that the outcomes for Sweden or America are much better. If only Britain would do more doctoring then everything would be okay.

Here is one of the studies that is sometimes referred to. One-Year Survival of Extremely Preterm Infants After Active Perinatal Care in Sweden.

This suggests that Swedish neonates have much better survival rates that in the UK. About 10% of 22 weekers survive, and about 50% of 23 weekers survive.

I spoke to one of the authors, Professor Karal Marsal, about why this might be. Simply, he wasn’t sure. It might that the Swedes have different protocols on delivery, they might be more interventional in the delivery room. This is mentioned in the paper. But certainly another reason was the ‘background population’.

Britain simply has a very different group of mothers giving birth to these neonatal babies than the Swedes. He said they have basically almost no teenage mothers, and yet that is one of the groups prone to preterm labour in the UK is just this one. And we have high rates of teenager motherhood. Also if you look at the Eurostat data cited above, about 17 per cent of British mothers smoke during pregnancy, whilst less than half that percentage in Sweden. Similarly, 91 per cent of Swedish women visit their doctor during the first trimester of pregnancy whereas only 65 per cent of British women do.

It seems likely that if you have a more health aware and more active cohort of mothers, who give birth at much lower rates of prematurity, then the health of their offspring is also likely to be better. And therefore the survival of neonates born in extreme prematurity would be better.

Professor Liz Draper also told me that comparing cohorts between countries is also very difficult. Sometimes it is difficult to compare like with like.